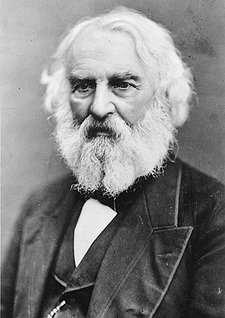

This year in Maine we are celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, America’s most famous poet in the 19th century. Longfellow is not my favorite Maine poet (that honor belongs to Edna Millay), but I am getting caught up in the festivities. Longfellow looms large in Portland, the city of his birth (we ignore the fact that he turned his back on Maine and spent most of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts). Each day I pass by his stately monument in Longfellow Square, across from the Wadsworth-Longfellow House, just down the block from Longfellow Books.

Today, Longfellow is by and large ignored in America, although he was a true rock star of his age. Even so, most older Americans will have read Hiawatha, and even school children today know Paul Revere’s Ride. In Germany, Longfellow is virtually unknown, although a German translation of Hiawatha is still in print. But there was an interesting transatlantic friendship that changed the course of Longfellow’s career and represents an important chapter in German-American literary influence.

Longfellow was an accomplished linguist. Like nearly every serious American scholar in those days he made several pilgrimages to Europe. In 1842 Longfellow was in Germany on a trip to recover from the death of his wife Mary, consoling himself with German romantic poetry. In Cologne he happened to pick up a volume of poetry by Ferdinand Freiligrath, a prominent voice of the radical Junges Deutschland group of writers. Shortly after that, Freiligrath traveled through Marienburg, where Longfellow was taking a water cure, and the two poets quickly became good friends.

Through Freiligrath the apolitical Longfellow was introduced to poetry as a political instrument. Freiligrath’s commitment to freedom and social justice had an immediate impact on Longfellow. The two began a correspondence (in both English and German), and fortunately more than 50 letters have been preserved at the Harvard University archives. A couple of the letters are available online, and they clearly show Freiligrath’s strong influence influence over Longfellow. On the return voyage back to Boston Longfellow penned his poems against slavery -which were to be so influential for the abolitionist cause in America – and the American poet acknowledged his indebtedness to his German friend in a letter:

During this time I wrote seven poems on Slavery. I meditated upon them in the stormy, sleepless nights, and wrote them down with a pencil in the morning. A small window in the side of the vessel admitted light into my berth; and there I lay on my back, and soothed my soul with songs. I send you some copies. In the "Slave’s Dream" I have borrowed one or two wild animals from your menagerie!

In one his most powerful slavery poems, The Warning, Longfellow invokes the image of the shackled slave and presages the conflagration that would engulf America 20 years later:

Beware! The Israelite of old, who tore

The lion in his path,–when, poor and blind,

He saw the blessed light of heaven no more,

Shorn of his noble strength and forced to grind

In prison, and at last led forth to be

A pander to Philistine revelry,–Upon the pillars of the temple laid

His desperate hands, and in its overthrow

Destroyed himself, and with him those who made

A cruel mockery of his sightless woe;

The poor, blind Slave, the scoff and jest of all,

Expired, and thousands perished in the fall!There is a poor, blind Samson in this land,

Shorn of his strength and bound in bonds of steel,

Who may, in some grim revel, raise his hand,

And shake the pillars of this Commonweal,

Till the vast Temple of our liberties.

A shapeless mass of wreck and rubbish lies.