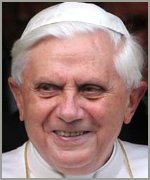

Pope Benedict has issued his third encyclical – Caritas in veritate

(Charity in Truth) – which addresses the global economy and its

inequalities. It is a long, dense piece and can be downloaded from the Vatican's Web site (English,Deutsch) .

The encyclical is sure to generate a great deal of controversy, since

the pope is calling for nothing less than a new economic order based on

economic justice and a more equitable distribution of wealth.

Its publication is obviously timed to coincide with the G8 and the

summit’s focus on economic repair, aid to poor countries, food security

and climate change.

Economics, Pope Benedict writes, is not just the pursuit of profits,

but must be based on an ethical pursuit of the "common good".

Profit is useful if it serves as a means towards an end that

provides a sense both of how to produce it and how to make good use of

it. Once profit becomes the exclusive goal, if it is produced by

improper means and without the common good as its ultimate end, it

risks destroying wealth and creating poverty.

He decries the "corruption" of the political class (not just in the

wealthy countries) and the unethical behavior of financiers and their

institutions as well as the exploitation of workers by multinational

corporations.

Corruption and illegality are unfortunately evident in the conduct

of the economic and political class in rich countries, both old and

new, as well as in poor ones. Among those who sometimes fail to respect

the human rights of workers are large multinational companies as well

as local producers. International aid has often been diverted from its

proper ends, through irresponsible actions both within the chain of

donors and within that of the beneficiaries. Similarly, in the context

of immaterial or cultural causes of development and underdevelopment,

we find these same patterns of responsibility reproduced. On the part

of rich countries there is excessive zeal for protecting knowledge

through an unduly rigid assertion of the right to intellectual

property, especially in the field of health care. At the same time, in

some poor countries, cultural models and social norms of behaviour

persist which hinder the process of development.

In a passage sure to displease the editors of the Wall Street

Journal, the Pope calls for an equitable distribution of wealth and

protection of workers' rights in every nation:

Lowering the level of protection accorded to the rights of workers,

or abandoning mechanisms of wealth redistribution in order to increase

the country's international competitiveness, hinder the achievement of

lasting development.

It is important to emphasize that Pope Benedict is not calling for a

wholesale socialization of the world economy: he recognizes the power

of markets in wealth creation. But he is highly critical of the

neo-liberal ideal of the unfettered markets. Markets must be regulated

in a "God-centered" economy for the common good. Benedict even goes so

far as to advocate a new supranational governing body to oversee and

enforce a more just global distribution of wealth and protect poorer

nations.

This seems necessary in order to arrive at a political, juridical

and economic order which can increase and give direction to

international cooperation for the development of all peoples in

solidarity. To manage the global economy; to revive economies hit by

the crisis; to avoid any deterioration of the present crisis and the

greater imbalances that would result; to bring about integral and

timely disarmament, food security and peace; to guarantee the

protection of the environment and to regulate migration: for all this,

there is urgent need of a true world political authority

Pope Benedict has written a very provocative piece with his Third

Encyclical. I don't agree with everything here, but the central

argument strikes me as correct and just – far more radical than any

"solutions" put forward by US politicians – Republican OR Democrat (who

would dare speak openly about wealth redistribution?).

Caritas in veritate lacks the passion and visionary power of Deus caritas est (God is Love – Benedict's first encyclical), and I miss the broad discussion of Western philosophy of the second encyclical (Spe Salvi – In hope we are saved). But I disagree with the assessment of Matthias Drobinski in Sueddeutsche Zeitung – Der weltfremde Papst . Dobrinski calls this encyclical a "disappointment" (Enttäuschung) and sees Benedict as being "out of touch" (weltfremd). On the contrary, Caritas in veritate displays an impressive grasp of complex economic issues – from hedge funds to globalization and business process outsourcing.