My last post on the story from Austria of Josef F. who kept his own daughter hidden in his cellar along with the children he fathered with her has inspired me to write about the novel DIe Kinder von Wien (The Children of Vienna) about six children living in a bombed-out cellar in postwar Vienna.

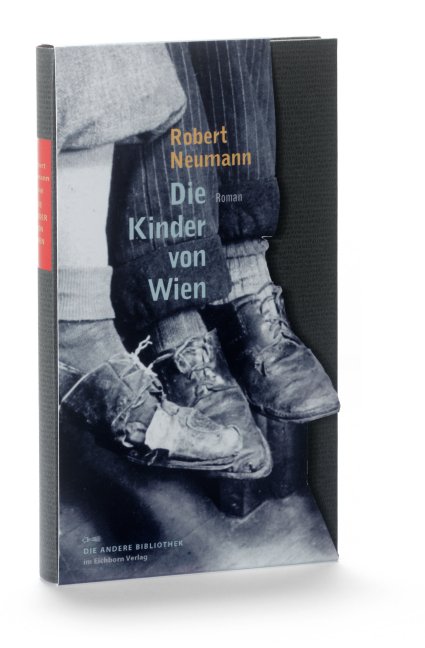

The good people at Eichborn Verlag in Frankfurt have reissued this important document of the postwar era and were kind enough to send me a review copy. DIe Kinder von Wien is actually Robert Neumann’s own 1974 translation of the original book in English: The Children of Vienna was published by Neumann in London in 1946. I have been unsuccessful in locating a copy of the original English novel, but hopefully this reissue by Eichborn and renewed interest in Neumann will lead to a new edition.

It was Heinrich Böll who created the genre of Trümmerliteratur (literally Rubble Literature) – literature about the shattered lives and shattered illusions in the immediate postwar period, as Germany lay in ruins. Die Kinder von Wien is a true example of Rubble Literature: the entire novel takes place in a ruined cellar, its entrance blocked by pile of rubble from the firebombing of Vienna. But the novel is also one of the few contemporary works of fiction to deal directly with the occupation: American and Soviet military personnel make appearances. (The best Occupation Novel in German is Wolfgang Koeppen’s Tauben im Gras which deals with the American occupation of Munich).

DIe KInder von Wien is the story of six children from different parts of the Reich, who, in the chaos of the war somehow found each other and created a semblance of a family in the ruins of Vienna. The leader – or father – of the group is the 13-year old Jid, a survivor of a concentration camp who has the physical stature of a 10-year old but the "eyes of a 35- or 55-year old." the 15-year old Ewa, a sometime prostitute, her friend Ate, a passionate Nazi and former member of the BDM (Bund Deutscher Maedel – the Nazi youth group for girls), a dull-witted 14-year old thief, Goy, from the Kinderverschickungslager (Childrens’ Relocation Camp – where they were sent to escape the bombing) and the "owner" of the cellar, the 7-year old Curls. Together they care for a toddler – Kindl – whose belly is hideously extended (Ballonbauch) due to severe malnutrition. They survive by selling their bodies stealing, bartering, and just by their wits.

When adults appear, they are almost alway a threat: they are intent on sexually abusing the children, or stealing what few possessions they have. So when the black US military chaplain – the Reverend Hoseah Washington Smith – appears in the cellar, the children assume he has come for sex with Ewa. But Smith has actually come to help them- something the children have never experienced in their lives. Slowly they open up to him and he gains their trust. Smith is another example of the fascination with the black American occupying forces. Koeppen’s Tauben im Gras features two black American soldiers: the noble savage Odysseus Cotton and the good-hearted but naive Washington Price. Robert Neumann’s Hoseah Washington Smith is also a noble fool: noble in his fervent desire to rescue the children, a fool to think he can bing light into a nightmarish world.

What is really compelling about DIe Kinder von Wien is the unusual language. Robert Neumann was a parodist by profession, and therefore a virtuoso on exactly reproducing dialects and language styles. So the children speak a Kauderwelsch of German, Yiddish, American slang, Russian slang, etc. In his forward to the German edition, Neumann writes about the difficulties in translating ("eindeutschen") this linguistic goulasch, which also universalizes the story of the children:

"Sie haben deutsch gesprochen, gemischt mit Jiddisch, gemischt mit American Slang und Popolski und Russian Slang, damls, dort, in dem Keller in Wien. Es kann aber auch ein anderer Keller gewesen sein anderswo, es kann jeder Keller gewesen sein überall, damals Anno fünfundvierzig, jenseits von dem Meridian der Verzweiflung."

The Eichborn edition contains an excellent biographical sketch of Neumann by Ulrich Weinzierl, which alone is worth the price of the book. Neumann was an immensely talented and difficult writer, who had a genius for making enemies – such as Erika Mann and Carl Zuckmayer, just to name a couple. That is no doubt an occupational hazard for a satirist and parodist. But the vitriol has probably contributed to Robert Neumann’s relative obscurity. Hopefully this new edition of DIe Kinder von Wien will turn the tide and his work will become more widely available.

Finally, the book includes photographs of bombed-out Vienna by the Austrian-American photographer Ernst Haas (1921-1986). The images of devastation and suffering set the tone for this remarkable book.