The AP has a report on the holocaust archive at Bad Arolsen in central Germany managed by the

International Tracing Service (ITS – part of the International Red Cross). Buried in the 16 miles of files are the stories of 17 million victims who were detained and, in many cases, murdered in 20,000 camps and ghettos of various categories:

“If you sat here for a day and read these files, you’d get a picture of what it was really like in the camps, how people were treated. Look — names and names of kapos, guards — the little perpetrators,” he said.

Moved to this town in central Germany after the war, the files occupy a former barracks of the Waffen-SS, the Nazi Party’s elite force. They are stored in long corridors of drab cabinets and neatly stenciled binders packed into floor-to-ceiling metal shelves. Their index cards alone fill three large rooms.

Mandated to trace missing persons and help families reunite, ITS has allowed few people through its doors, and has responded to requests for information on wartime victims with minimal data, even when its files could have told more.

It may take a year or more for the files to open fully. Until then, access remains tightly restricted. “We will be ready any time. We would open them today, if we had the go-ahead,” said Blondel.

When the archive is finally available, researchers will have their first chance to see a unique collection of documents on concentration camps, slave labor camps and displaced persons. From toneless lists and heartrending testimony, a skilled historian may be able to stitch together a new perspective on the 20th century’s darkest years from the viewpoint of its millions of victims."

I can’t understand why the archive is not opened immediately now – at least to survivors and relatives of the victims; why isn’t there a big international push to digitize the archive and make it available on the Web? The immediate familes of the victims and witnesses are dying off and the names will be forgotten.

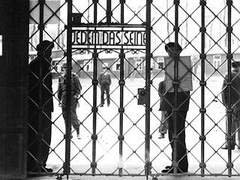

One name that will never be forgotten is Jack Werber, a survivor of the slave camp at Buchenwald. In the closing days of the war, Jack Werber managed to thwart the transport of 700 boys to the death camps in Poland:

"Mr. Werber, a son of a Jewish furrier from the Polish town of Radom, was the barracks clerk at Buchenwald in August 1944 when a train carrying 2,000 prisoners arrived, many of them young boys. By then, with the Russians advancing into Germany, the number of Nazi guards at the camp had been reduced. Working with the camp’s underground — and with the acquiescence of some guards fearful of their fate after the war — Mr. Werber helped save most of the boys from transport to death camps by hiding them throughout the barracks."

Mr Werber was one of only eleven survivors from a group of 3,200 men sent to Buchenwald in 1939. He eventually made his way to America, where he was successful entrepreneur. Jack Werber died earlier this week on Long Island, New York; his life is a testimony to the power of what one courageous individual can achieve. The fate of the other 3,189 men who arrived with him at Buchenwald and perished is buried in the archives at Bad Arolsen.