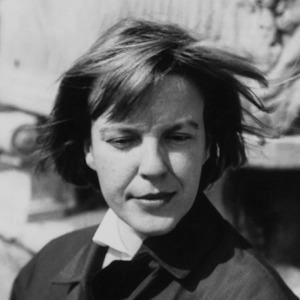

Continuing the observance of National Poetry Month, I want to shift from the tiresome controversy around Günter Grass and his bad poem to celebrate one of the truly great postwar poets. In 1955 Henry Kissinger, then a professor at Harvard, invited a group of talented young Europeans to participate in a summer seminar. This would be Ingeborg Bachmann's only visit to America, and before traveling up to Cambridge she spent time at the Mansfield Hotel in Manhattan, just blocks away from the Mad Men of Madison Avenue, who were propelling the nation headlong into the advertising age. Bachmann's brief stay in Manhattan would bear fruit with her famous radio play Der gute Gott von Manhattan ("The Good God of Manhattan") and the beautiful poem Harlem.

In one of her last poems, Reklame ("Advertisement" – 1956), Bachmann brilliantly shows how the slogans of the Mad Men with their false promises of eternal happiness disrupt the poet's confrontation with her own mortality. The ever-louder Musik, reaching a crescendo with the neologism Traumwäscherei ("Dream-Laundry"), drowns out but cannot slow the inexorable movement towards the death-silence (Totenstille).

(English translation by Peter Filkens after the break).

Reklame

Wohin aber gehen wir

ohne sorge sei ohne sorge

wenn es dunkel und wenn es kalt wird

sei ohne sorge

aber

mit musik

was sollen wir tun

heiter und mit musik

und denken

heiter

angesichts eines Endes

mit musik

und wohin tragen wir

am besten

unsre Fragen und den Schauer aller Jahre

in die Traumwäscherei ohne sorge sei ohne sorge

was aber geschieht

am besten

wenn Totenstilleeintritt

-Ingeborg Bachmann

Advertisement

by Ingeborg Bachmann

But where are we going

carefree be carefree

when it grows dark and when it grows cold

be carefree

but

with music

what should we do

cheerful and with music

and think

cheerful

in facing the end

with music

and to where do we carry

best of all

our questions and dread of all the years

to the dream laundry carefree be carefree

but what happens

best of all

when dead silence

sets in

tranlated by Peter Filkins

0 comment

Great poem. Almost Celan-esque in the rhyme.

Good observation. But Bachmann wouldn’t resume her on-again, off-again affair with Celan until a year after Reklame was written.

Both Celan and Bachmann were very much influenced by Heidegger’s inventive use of German language.